Introduction

In its Made In China 2025 initiative, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) detailed its plan to fully integrate itself into the global manufacturing chain and broaden control of strategic geographic locations. These plans are driving its expansion into the Arctic and Antarctic. On 19 November 2014, the PRC Party Secretary & Director of the State Oceanic Administration stated that China is destined to be a “great polar power” by 2030. China has launched expeditions and established research facilities in both the Arctic and Antarctic, strengthening their influence in polar affairs and shaping the evolving geopolitical landscape. Beyond scientific exploration, China’s growing presence in these remote frontiers aligns with its broader strategic and military objectives. In the Arctic, melting ice sheets pose global challenges, but Beijing also sees opportunities. China leverages scientific and commercial ventures to influence governance, access natural resources, and establish new shipping routes, despite lacking sovereign jurisdiction. Emerging shipping routes could shorten trade transit times and improve regional resource access. However, lacking sovereign territory in the Arctic, China relies on partnerships with other nations to advance its interests.[1],[2],[3]

China’s expansion into the polar regions, as part of their Science of Military Strategy, reflects a calculated effort to enhance its global influence and military capabilities, posing significant challenges to U.S. national security and the Department of Defense (DoD). Tied to its military-civil fusion (MCF) strategy, China’s Arctic research raises security concerns. Arctic research enhances China’s knowledge of submarine operations, icebreaker navigation, and undersea communication cables, which are crucial for military strategy.[4],[5]

China’s History and Strategy in the Antarctic

China’s growing presence in Antarctica is part of its broader polar strategy, combining scientific research and geopolitical influence, but it is also advancing the potential for dual-use infrastructure. In 1980, China began preparing for its Antarctic scientific research program, initially sending scientists to participate in foreign expeditions, and signed the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) on 09 June 1983. Since its first Antarctic expedition in 1984, China has methodically expanded its footprint, establishing multiple research stations, deployed advanced icebreakers, and leveraged its role within the ATS to increase its influence. This led to the construction of the Great Wall Station in 1985, located on King George Island off the Antarctic Peninsula. It was China’s first Antarctic research station and served as a logistics and research hub.[2],[3]

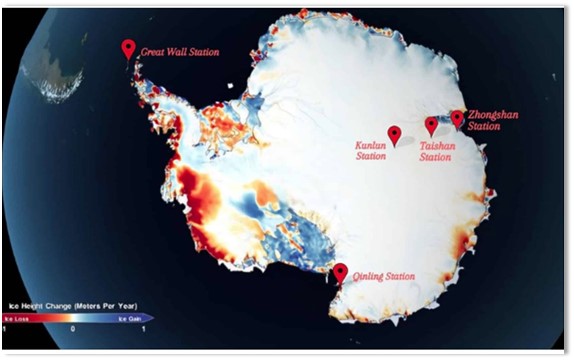

As highlighted in Figure 1, China operates five (5) stations in the Antarctic. The graphic also illustrates the ice height change in meters per year.

Figure 1 – Map of Chinese Antarctic Stations[6]

Zhongshan Station, built in 1989, is situated in East Antarctica’s Larsemann Hill and expanded China’s operational capabilities further inland. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, China had solidified its Antarctic presence, establishing itself as a Consultative Party to the ATS and securing voting rights on Antarctic governance. From 2001 through 2020, China transitioned from scientific research to strategic interests. This was China’s most significant pivot in the region. Kunlun and Taishan Stations, built in 2009, continued their inland-focused research stations, strengthening China’s ability to conduct year-round research and extending its strategic reach. Kunlun Station, built at Dome A, the highest point of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, has ideal conditions for astronomical observations, climate research, and satellite tracking. Its remote location also raises concerns over potential dual-use applications, such as surveillance and space-based intelligence gathering.[1],[2],[4]

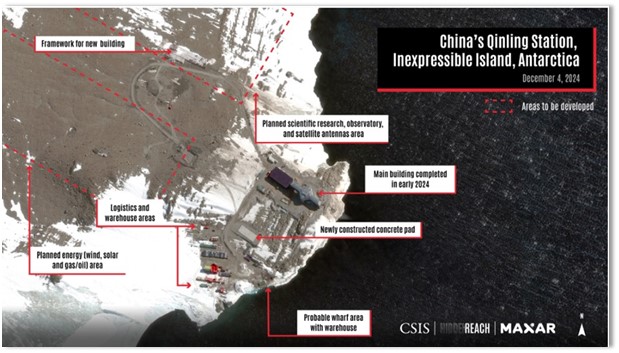

In early 2024, China completed Qinling Station, its fifth permanent Antarctic research station on Inexpressible Island in Terra Nova Bay in the Ross Sea. This location is strategically significant because it is near McMurdo Sound, which is home to the U.S. McMurdo Station and New Zealand’s Scott Base, which are two (2) of Antarctica’s most important Western research hubs. Its proximity to major Antarctic shipping lanes, which have been cleared of ice by the Xuleong and Xuelong 2 icebreakers, suggests China intends to monitor and engage in long-term regional activities. While officially a scientific research station, Qinling Station’s infrastructure raises concerns about potential military applications, including satellite and electronic surveillance due to its location near key U.S. and allied research stations. Its locations allow for naval logistics support, providing a foothold near important sea routes that may become commercially viable as Antarctic ice melts. The deep-sea research facilities it has could also aid underwater surveillance, submarine warfare research, and oceanographic intelligence gathering.[1],[6]

Figure 2 – The Icebreaker Xuleong 2 (‘Snow Dragon’),[7]

Figure 3 – China’s Fifth Antarctic Research Station, Qinling Station[1]

China is constructing a sixth Antarctic research station on the Amery Ice Shelf in East Antarctica, which is expected to be operational in 2025. The Amery Ice Shelf is a critical gateway for inland Antarctic expeditions, and its location offers strategic advantages for both scientific and potential military applications. When completed, China will have the second-largest presence in Antarctica after the U.S., further solidifying its long-term strategic ambitions in the region. The station could enhance China’s global satellite navigation system (BeiDou), which has applications for civilian and military operations. While the ATS bans new territorial claims, China’s expanding infrastructure suggests it is positioning itself for future negotiations, should the ATS be renegotiated or challenged. Open-source research indicates China has conducted seabed mapping and resource assessments, which could have implications for future Antarctic mineral and energy exploration and exploitation.[5],[8],[9]

China’s Growing Presence in the Arctic

China has steadily increased its presence in the Arctic, despite not being an Arctic nation. It has pursued a multifaceted strategy to gain influence over Arctic governance, access natural resources, and leverage emerging shipping lanes to advance its economic and strategic interests. By branding itself as a “Near-Arctic State,” China has sought to legitimize its role in Arctic affairs, expanding scientific research, commercial partnerships, and infrastructure projects while also raising concerns over its potential strategic and military ambitions.[10],[11]

In 2022, geopolitical shifts accelerated as PRC President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin reaffirmed their cooperation, including the Polar Silk Road (PSR), just before Russia invaded Ukraine. Initially announced in 2017, the PSR was seen as a key pillar of Russo-Chinese Arctic collaboration. Climate change is rapidly reducing Arctic Sea ice, making shipping lanes more viable for commercial transit. China views these routes as a shortcut that could significantly reduce shipping times and costs between Asia and Europe. In 2018, the PRC officially incorporated Arctic shipping routes into its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[12],[13],[14]

- The Northern Sea Route runs along Russia’s Arctic coastline, reducing transit times between China and Europe by up to 40% compared to the Suez Canal. China has engaged in joint ventures with Russian companies to gain access to this route.[12]

- The Transpolar Sea Route is a potential future route running directly across the Arctic Ocean, which would further reduce transit times but is currently too ice-covered to be fully operational.[12]

- The Northwest Passage runs through Canada’s Arctic waters. However, China does not recognize Canada’s sovereignty over the passage. Beijing has sent research missions to assess the route’s feasibility.[12]

- The Arctic Bridge Route is a seasonal route connecting the Russian port of Murmansk and the Canadian port of Churchill, Manitoba.[12]

Figure 4 below illustrates a map of the Arctic Sea routes.

Figure 4 – Arctic Sea Routes[15]

The links between China’s polar research programs and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) have sparked concerns over potential security threats in the Arctic. A key example of this occurred with Sweden, where China established its first overseas satellite ground station at the Esrange Space Center near Kiruna in 2016. In 2020, the Swedish Space Corporation (SSC), which oversees Esrange, chose not to renew its contracts with China due to fears that the facility could support military intelligence and surveillance operations. This decision extended beyond Esrange, affecting China’s access to other SSC-managed ground stations in South America and Australia. However, the exact timeline for contract expirations and whether China’s access to the stations has been completely revoked remains uncertain. DoD leadership has echoed these security concerns. A 2019 DoD report warned that China’s civilian research could contribute to an expanded military presence in the Arctic, while the 2022 U.S. administration’s Arctic strategy highlighted China’s use of scientific activities for dual-use research with military and intelligence applications.[1],[16]

China’s Science of Military Strategy asserts that military-civilian pursuits are the path to polar power, and implementing dual-use applications of polar science will assist in achieving it. For example, it is believed the polar observation satellites, under the auspices of providing polar ice assessments, are also being used to provide intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) to the PLA. Another example of this dual-use is the scientific application of weather balloons to provide data on upper atmospheric conditions, which the PLA also uses for ISR and command and control. Acknowledging these growing concerns, several countries and governmental bodies (Canada, the European Commission) have passed legislation and regulatory measures limiting (or ending) China’s investment in their regional infrastructure. The DoD published the 2024 DoD Arctic Strategy, nested under the 2022 National Security Strategy, addresses its intentions and potential moves to combat this growing area of concern.[10],[17],[18]

China’s continued expansion into the Arctic has also created a geopolitical destabilizing alliance with Russia. China has long seen Russia as a key entry point into the Arctic, though the latter has historically resisted its growing presence due to national security concerns. Moscow initially opposed China’s observer status in the Arctic Council and restricted its research activities along the Northern Sea Route. However, the war in Ukraine has left Russia increasingly isolated, making it more dependent on Chinese investments in infrastructure and technology. As the Arctic Council faces uncertainty, China has deepened its strategic focus on Russian ports. In 2019, Chinese academics from two (2) state universities conducted studies to identify which Russian key access points along the Northern Sea Route gave the most access to the region. The report ranked 13 Russian ports based on five (5) primary factors: natural conditions, infrastructure, port operation, interior environment, and geographic location. Since the release of the report, Beijing has invested approximately $130 billion in the infrastructure of the ports.[1],[19]

Conclusion

While China officially frames its Antarctic expansion as purely scientific, the dual-use potential of its research stations, logistical infrastructure, and technological capabilities raises questions about its broader ambitions. The completion of Qinling Station in 2024 and the upcoming sixth research station in 2025 are significant steps in China’s long-term Antarctic strategy, increasing its presence near key geopolitical locations. With growing tensions between Washington and Beijing and concerns over the future of the ATS, China’s Antarctic expansion represents a critical geopolitical development that will shape the future of polar governance, global strategic competition, and scientific research in one of the world’s last frontiers.[20],[8]

The 2024 DoD Arctic Strategy states that climate change and shifts in the geostrategic environment propel the need for a new approach to the Arctic. China’s growing presence there is driven by long-term strategic objectives that go far beyond scientific research. By leveraging economic partnerships, scientific research, and infrastructure investments, Beijing is actively positioning itself as a major player in Arctic governance, resource extraction, and commercial shipping. However, its ambitions are increasingly met with resistance from Arctic nations, particularly the U.S., Canada, and Nordic countries. They fear China’s Arctic engagement may be a precursor to greater geopolitical and military involvement. As the Arctic continues to thaw, China’s role in shaping the future of the region will be a major point of contention in global politics, one that will likely escalate as competition over resources, trade routes, and strategic influence intensifies.[10],[21]

[1] Funaiole, M. P., Hart, B., Powers-Riggs, A., Jun, J., & Bermudez, J. S., Jr.. (2024, December 19). China Makes Progress On Its Fifth Antarctic Research Station. Center For Strategic & International Studies. Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/analysis/china-makes-progress-its-fifth-antarctic-research-station.

[2] Cigui, L. (2014, November 19). From A Polar Power to Great Polar Power. Chinese Ministry of Land & Resources. Retrieved from https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2014-11/19/content_2780849.htm.

[3] Institute for Security & Development Policy. (2018, June). Made In China 2025. Institute for Security & Development Policy. Retrieved from https://www.isdp.eu/wp- content/uploads/2018/06 /Made-in-China-Backgrounder.pdf

[4] Tianling, X., Yaoling, L., & Wuchao, K. (2020). The Science of Military Strategy. China Aerospace Studies Institute. Retrieved from https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Tra n slations/2022-01-26%202020%20Science%20of%20Military%20Strategy.pdf

[5] Funaiole, M. P., Hart, B., Powers-Riggs, A., Jun, J., & Bermudez, J. S., Jr..)2023, April 18). Frozen Frontiers: China’s Great Power Ambitions in the Polar Regions. Center For Strategic & International Studies. Retrieved from https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/china-polar-research-facility/.

[6] Blesic, J. (2024, May 15). Chinese Presence in Antarctica as a New Geopolitical Challenge. The Center For Geostrategic Research & Terrorism (Poland). Retrieved from https://cegit.org/chinese-presence-in-antarctica-as-a-new-geopolitical-challenge/

[7] The Arctic Gateway. (2024). Xuelong 2. ArcticPortal.org. Retrieved from https://arcticportal.o rg/shipping-portlet/icebreakers/snow-dragon.

[8] The People’s Republic of China. (2024, November 21). Cargo Vessel Sets Sail For China’s 41st Antarctic Expedition. The State Council of The People’s Republic of China. Retrieved from https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202411/21/content_ WS673fcab9c6d0865f4e8ed4d7.html.

[9] The Antarctic Treaty. (n.d.). Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty. Retrieved from https://www.a ts.aq/dev https://www.ats.aq/devAS/Parties?lang=e

[10] Pechko, K. (2025, January 7). Rising Tensions and Shifting Strategies: The Evolving Dynamics of US Grand Strategy in the Arctic. The Arctic Institute Center For Circumpolar Security Studies. Retrieved from https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/rising-tensions-shifting-strategies-evolving-dynamics-us-grand-strategy-arctic/

[11] U.S. Secretary of Defense. (2024). 2024 Arctic Strategy. U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved from https://media.defense.gov/2024/Jul/22/2003507411/-1/-1/0/DOD-ARCTIC-STRATEGY-2024.PDF

[12] Lamazhapov, E., Stensdal, I., & Heggelund, G. (2023, November 14). China’s Polar Silk Road: Long Game or Failed Strategy?. The Arctic Institute Center For Circumpolar Security Studies. Retrieved from https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/china-polar-silk-road-long-game-failed-strategy/

[13] Fleck, A. (2023, June 15). The Polar Silk Road. Statista. Retrieved from https://www.statista .com/chart/30201/major-maritime-routes-opening-up-in-the-arctic/

[14] Eiterjord, T. (2023, November 23). What the 14th Five-Year Plan says about China’s Arctic Interests. The Arctic Institute Center For Circumpolar Security Studies. Retrieved from https://www. thearcticinstitute.org/14th-five-year-plan-chinas-arctic-interests/

[15] Drycrz, C. (2017, December). Safety of Navigation in the Arctic. Polish Naval Academy. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Northwest-Passage-the-Northeast-Passage-and-the-Northern-Sea-Route-and-the_fig6_321687663

[16] Parsonson, A. (2025, January 4). Swedish Military to Serve as Anchor Customer for Esrange Space Center?. European Spaceflight. Retrieved from https://europeanspaceflight.com/swedish-military-to-serve-as-anchor-customer-for-esrange-space-center/

[17] U.S. House of Representatives. (2024, October 16). Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party. Congress of the U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved from https://selectco mitteeontheccp.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/10.16.24_PRC%20dual%20use%20research%20in%20the%20Arctic__.pdf

[18] Pezard, S., Chindea, I. A., Aoki, N., Lumpkin, D., & Shokh, Y. (2025, January 23) China’s Economic, Scientifc, & Information Activities In The Arctic – Benign Actvitites or Hidden Agenda. RAND Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2823-1.html.

[19] Zhang, J. (2024, December 9). Russia Clears Path for China in the Arctic. Geopolitical Intelligence Services. Retrieved from https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-arctic-russia/

[20] The Antarctic Treaty. (n.d.). The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty. Retrieved from https://www.ats.aq/e/protocol.html

[21] Menchew, B., Mahle, L., Ghosh, P., & Sistla, M. (2024, December 10). Polar Infrastructure And Science For National Security: A Federal Agenda To Promote Glacier Resilience And Strengthen American Competitiveness. Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved from https://fas.org/pub lication/polar-infrastructure/