Introduction

On 20 January 2025, Executive Order 14157 redesignated certain drug cartels and transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) as foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) and specially designated global terrorists (SDGTs). Under E.O. 14157, the United States Department of State redesignated Tren de Aragua (TdA), Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13), the Sinaloa Cartel, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), the Northeast Cartel (CDN), the New Michoacán Family (LNFM), United Cartels (CU), and the Gulf Cartel (CDG) as such.[1]

Overview

TdA has operations in the U.S., Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Chile, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Brazil. The organization is involved in kidnappings, extortion, bribery, targeted assassinations, and has sanctioned the killing of American law enforcement officials. MS-13 has operations in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, and within the U.S. The group has conducted targeted assassinations and IED bombings against both government officials and civilians in El Salvador, where the group controls territory through violent intimidation. The Sinaloa Cartel in Sinaloa, Mexico, has also committed murders, kidnappings, and intimidation of government officials and civilians. The Sinaloa Cartel brings large quantities of illegal drugs, including fentanyl, into the U.S. CJNG is based in Mexico but has connections in the Americas, Australia, China, and Southeast Asia. The cartel is involved in extortion, theft of oil and minerals, migrant smuggling, the arms trade, and drone strikes against Mexican law enforcement and military personnel, along with targeted assassinations against Mexican officials. CDN is present in northeastern Mexico and has perpetrated attacks against government officials. The group also engages in kidnapping, extortion, human smuggling, and drug trafficking. LNFM is based in several Mexican states and has attacked government officials using explosives and unmanned aircraft system (UAS) strikes. LNFM is also involved in kidnapping, extortion, and drug trafficking. CDG has operations in northeast Mexico where it engages in kidnapping, extortion, human smuggling, drug trafficking and assassinations of government officials and civilians. CU is composed of multiple cartels in Michoacán, Mexico; the organization has been involved in the death of military and law enforcement personnel, along with civilians.[2]

Background

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), TCOs are groups that engage in organized illegal activity for profit. Ideological concerns are usually secondary. Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) are designated in accordance with sections of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) and meet the following standards: being a foreign organization, engaging or having the capability or intent to engage in terrorism or supporting activity, and threatening U.S. national security or American nationals. An FTO designation is intended to impede funding for terrorism, isolate an organization, deter transactions with the named FTO, increase public awareness, and garner support from other nations and governments. FTOs are generally subject to more significant penalties than TCOs.[3],[4],[5],[6]

As these respective types of organizations have evolved their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), there has been a growing convergence between TCOs and FTOs. The line between an act of terror and a criminal act is increasingly blurred. TCOs that are not driven by ideologies like traditional terrorist organizations still have the motivation to act in ways that parallel them. Section 140 (d)(a) of the Foreign Relations Authorization Act defines terrorism as an act of violence that is both politically motivated and premeditated. Cartels in Mexico have been intertwined in Mexican politics for decades, fostering or forcing advantageous circumstances for their illicit activities. The political motivations for cartels can be distinguished from those of FTOs because they are a means to an end, which is to amass power and support their illegal operations. However, the recent designation of multiple TCOs as FTOs was ordered as a result of TTPs that mirror terrorist activity.[5],[7]

The majority of the TCOs designated as FTOs are based in Mexico. The rise of Mexican Transnational Criminal Organizations (MTCOs) is the culmination of both historical efforts by law enforcement and legitimate trade agreements. Several Colombian cartels were disrupted in the 1990s by U.S. and Colombian joint efforts to fight the drug trade in the Caribbean, leading to a transition in smuggling routes in which cocaine and methamphetamines traveled through Mexican terrain via area cartels. In 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico removed tariffs on legal trade but also facilitated illegal imports. The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) gained power through a centralized political system and became the dominant political party in Mexico for 71 years. The reigning PRI had, in effect, formerly controlled the reach of MTCOs to an extent by working with the cartels but also restraining their influence. The decline of the PRI in the 1980s and 90s led to a power struggle between cartels to seize plazas and take over drug markets. These factors led to the growth of sophisticated cartel monopolies throughout Mexico that mirror globalized conglomerates and operate as quasi-governmental organizations in certain areas. These cartels have established dominion over most illicit traffic through the U.S. southern border.[1],[7],[8]

Criminal and Terror Activity and Operations

Historically, many FTOs have been involved in drug trafficking, arms trafficking, and money laundering to finance their operations. For example, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) is a Marxist insurgency that has been designated by the U.S. government as an FTO due to its long-term involvement in bombings, kidnappings and assassinations. FARC has used drug trafficking to support its political activities and seize control over areas where populations are dependent on the cultivation and trade of illicit crops. FARC was already bringing in between $60 and $100 million annually by the 1990s. The Taliban originally became involved with drug trafficking to consolidate political power and now relies heavily on profits from illicit activity. The Afghan poppy trade was estimated to have brought in $416 million in 2020. Terrorist operations are expensive: recruitment, compensating members and informants, and purchasing equipment all require financing. Criminal enterprises bring in significant funds and simultaneously aid FTOs in guarding operations from detection. Drug trafficking constitutes an enormous revenue stream for these newly designated organizations, and profits in Mexico are estimated to be in between $30 to $35 billion a year. The designated FTOs have established relationships with American drug trafficking organizations to distribute and sell illicit substances, fueling both criminal violence and the overdose crisis in the U.S. In 2024, 84,076 Americans died from a drug overdose. Illicit activities by designated FTOs include, but are not limited to, drug trafficking, extortion, money laundering, theft of oil and gasoline, migrant smuggling, human trafficking, arson, and counterfeiting.[7]],[9],[10]

For the newly designated FTOs, drug trafficking has been used to fund military-grade weapons and training, all of which are necessary to intimidate, coerce, and threaten the public, the government, and other organizations. The CDN was recruited from the Mexican Army’s Airborne Special Forces Group (GAFEs) and the Guatemalan Kiabiles Special Forces. Both groups have sophisticated expertise in intelligence, communications and countersurveillance operations, as well as training in military-grade weapons and irregular warfare. This creates a climate where cartels resemble paramilitary forces rather than simply drug trafficking organizations. In many cases, the criminal activity of designated FTOs has grown to resemble traditional terror TTPs. For example, MTCOs leverage social media in a manner similar to al-Qaeda by recording and uploading videos depicting extreme violence. Extortion has also escalated to the point that the Mexican government has compared several incidents to acts of terror. On 25 August 2011, the CDN set fire to the Casino Royale San Jeronimo, which resulted in the death of 53 individuals, after the casino’s owners failed to make an extortion payment. These deliberately extreme and provocative acts of retaliation have a profound psychological impact on both the Mexican government and the public.[7],[11]

The recently designated FTOs also conduct targeted assassinations, bombings, and attacks on critical infrastructure as well as kidnappings. In order to secure their illicit operations and threaten competition, the Sinaloa Cartel has regularly been involved in kidnappings, leading to a State Department ban on government travel in states where the cartel is based. The frequency of kidnappings, assassinations, and other forms of extreme violence perpetrated by the Sinaloa cartel has had implications for both American security interests and foreign relations. The CDG kidnapped four (4) American citizens in 2023 and detonated explosives at a U.S. consulate in 2008. The JNGC assassinated the former Governor of Jalisco State, Aristoteles Sandoval, and has been connected to more than 100 assassinations of government officials in all three (3) branches of Mexican government. These assassinations and attacks demonstrate a threat to American national security interests by eliminating potential governmental allies in foreign relations and joint counter- drug-trafficking plans, as well as threatening cross-border trade. FTOs also use UAS to surveil and circumvent U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) operations, posing a threat to personnel, aircraft, and border security. Cartels within Mexico have even conducted drone strikes against both Mexican law enforcement and rival cartels in the past, raising the possibility of similar attacks against CBP assets or personnel.[7],[12],[13]

Complicity of Mexican Government and Law Enforcement

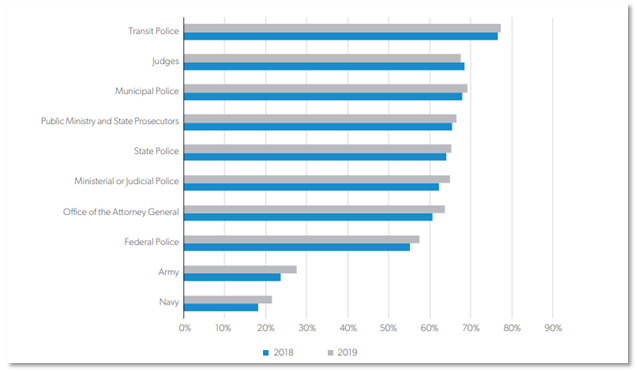

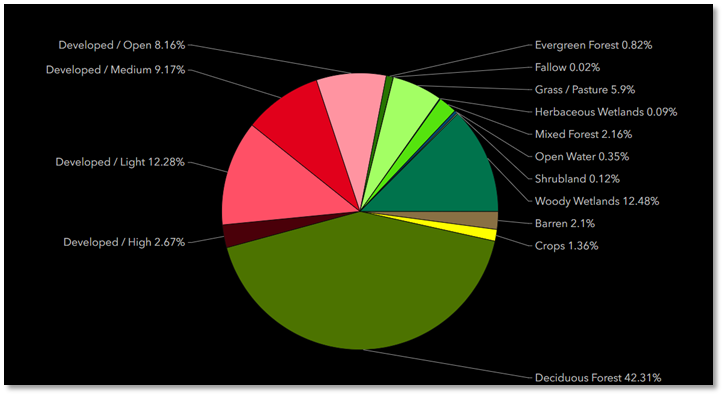

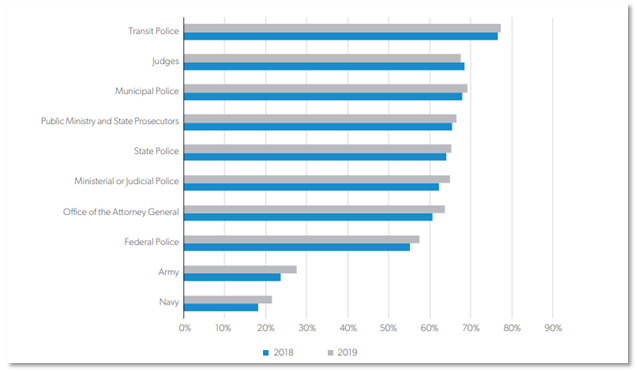

The wealth and capabilities of the cartels have grown substantially. Consequently, Mexican government and law enforcement agencies often lack the capacity to control them and sometimes become complicit in their dealings. De facto paramilitary groups using irregular warfare TTPs cannot easily be compared to the typical organized criminal gangs that law enforcement agencies are more qualified to handle. Bribery and corruption may also pose a threat, as cooperating law enforcement officials may impede investigations and diminish the general public’s confidence, leading to unreported crimes. An estimated 90% of crimes in Mexico go unreported, and between 72% and 77% of Mexican citizens believe the police are mostly or completely corrupt. In 2019, the largest survey on citizen perception of corruption, the Global Corruption Barometer, found that bribes were reported to have been taken in 52% of police cases that interacted with the surveyed Mexican population. This data was collected from individuals that had contact with police within the previous year.[7],[14],[15]

Figure 1 – Perception of Corruption in Mexican Institution[16]

Political corruption also puts U.S. and Mexican joint security measures at an impasse. Bilateral security cooperation is affected by a lack of trust on either side. For example, money generated by drug trafficking in the U.S. can be used by the newly designated FTOs to bribe government and security officials, who can, in turn, undermine American efforts to combat drug operations. In some cases, money laundering from corrupt Mexican officials is conducted through the U.S. by means of real estate and business transactions. Security cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico has been difficult in the past, illustrated by the collapse of the Mérida Initiative. After a Mexican defense minister was arrested on drug charges through an investigation by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency in 2020, Mexico’s parliamentary body, Congreso de la Unión, passed a law that requires foreign agents to report any intelligence they obtain to Mexican federal authorities, which restricted U.S. law enforcement operations. The Mérida Initiative, which sought to fight corruption in Mexico and combat drug, weapons, and bulk currency trafficking from the U.S. into Mexico, saw most of its programs come to a halt. The implications of the FTO designation may include increased tensions with Mexican officials as corruption cases will be increasingly scrutinized, potentially impeding cooperation and intelligence sharing. On the other hand, the designation could motivate the Mexican government to revert from its semi-isolationist posture concerning operations on the border so as to not let the U.S. make additional policy decisions without its input.[12],[16], [17],[18]

Statute 18 U.S.C. §2339B prohibits any “material support or resources” granted to FTOs and enforces civil or criminal penalties under U.S. counterterrorism designations. Material support statutes may apply regardless of impact on commerce and can reach beyond U.S. borders if dealings are committed outside of the country. Any transaction that provides material support between a citizen or an entity and an FTO may result in criminal penalties, whether or not a transaction was deliberate or had any material consequences. Material support is very broadly defined. Support can consist of financial resources, property, arms, personnel, documents, equipment, transportation, housing, counsel, as well as payments for extortion, protection, or ransom. While the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects the speech of American citizens, even verbal support for FTOs, material support of any kind is a crime.[19],[20]

In the past, by using the material support statute, the U.S. has been able to interrupt ISIS fundraising via false charities and cryptocurrency laundering. The U.S. Treasury Department, by 2020, froze over $22 million in assets that were associated with Hezbollah. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) used a wire transfer through a U.S. bank account and U.S. email accounts to prosecute French cement company Lafarge for providing material support to ISIS and the al-Nusrah Front, resulting in an agreement to pay $778 million in fines.[12],[19]

On 05 February 2025, U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi issued a memorandum that removed approval requirements to prosecute drug cartels on the basis of terrorism charges, expediting the process. This means that the Material Support statute and the Racketeer Influence Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act are much easier to leverage. The RICO Act permits civil lawsuits against individual entities within criminal organizations with more severe penalties. The RICO Act can also be used to penalize leading individuals in criminal groups, therefore directing penalties against and destabilizing entire organizations. By removing complex requirements, attorneys and prosecutors will possibly have more motivation to use these tools. However, the review process for RICO was formulated to establish universal usage of the act. This may lead to discrepancies in criminal and civil cases in terms of whether or not statutes are utilized. The DOJ’s National Security Division has also re-tasked anti-money laundering teams through the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and allocated forfeiture prosecutors to aid in drug trafficking and cartel cases.[21],[22], [23]

The recent FTO designation marks a transition in strategies for sanctions compliance among both U.S. and non-U.S. entities due to increased uncertainty over the gap of regulatory risk between legal frameworks for FTOs as compared to TCOs. The cartels have long been intertwined with Mexico’s economy. Front businesses, shell companies or other tactics to launder money may pervade many industries in areas such as agriculture, transportation, retail or real estate. American businesses run an elevated risk of breaking the law by interacting knowingly or unknowingly with FTOs that permeate these sectors. Financial institutions will likely develop a more mindful posture, as there is a significant increase in both of U.S. jurisdictional reach and unclarified questions within applicable statutes. The scope of the sanctions risk concern is wide-ranging and covers foreign subsidiaries of domestic companies, joint ventures, and international businesses.

Jurisdictional Implications and U.S. Agency Direction

The 1981 Executive Order 12333 on United States Intelligence Activities grants intelligence agencies the authority to gather intelligence outside of the U.S. Intelligence efforts are often determined by the priorities of the federal administration, which is currently focused on drug cartels across the border.[21],[26]

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) authorizes the interception of electronic signals through U.S. communications providers. As of 2024, Congress has re-authorized FISA to include counternarcotics when defining foreign intelligence. Section 702 of FISA permits the collection of foreign intelligence information from non-U.S. persons outside of the country. The designation of certain cartels as FTOs recognizes classified information associated with them as “foreign intelligence,” which is subject to Section 702 collection. Conversely, Title I of FISA may be more useful in investigations. Title I of FISA authorizes the collection of information from U.S. corporations or individual entities if the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) determines, by probable cause, that an intelligence target is an agent of a foreign power. FISA defines a foreign power as an organization involved in international terrorism, and FTO designations have been previously used to fulfill FISC requirements.[21],[27]

There are many other resources used in combating terrorist threats to the U.S. that have been leveraged following the designation. The Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF) was developed to disrupt transnational criminal organizations and was included in the President’s Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime, as well as Executive Order 13773, which gave the task force further direction. The OCDETF has focuses on narcotics and financial criminal activity. The International Organized Crime Intelligence and Operations Center (IOC-2) works closely with the OCDETF and has a component to investigate non-drug operations, which expands its purview over cartels. The FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTFs) coordinate through the National Joint Terrorism Task Force in efforts against terrorism and towards interagency collaboration. U.S. President Donald Trump issued orders to establish Homeland Security Task Forces (HSTFs) in all states for the purpose of dismantling criminal cartels. The HSTFs will be manned by agencies that also staff and contribute to OCDETF and JTTFs, facilitating intelligence sharing. Current operations Liquid Death and Take Back America are pooling the efforts of many U.S. agencies including the DEA, FBI, ICE-HIS and IRS CI, illustrating the current administration’s emphasis on its efforts to eliminate cartels.[21],[28],[29],[30],[31]

Outlook

The State Department’s aggressive expansion of FTO designations escalates the risks of operations and financing for these organizations. Money laundering networks may also become less effective or gain new vulnerabilities Cartel leadership may also face aggressive targeting. Designated FTOs may be forced to adopt more caution in recruiting new members. As of May 2025, two (2) individuals have been indicted under Material Support, money laundering and smuggling charges in South Texas connected to the CJNG. This indicates that the DOJ will likely escalate prosecutions related to the designated FTOs. U.S. businesses may engage in due diligence overhauls to ensure sanctions compliance based on the increased risk of exposure to Material Support statutes. Any direct or indirect involvement with designated FTOs has the potential for severe civil or criminal penalties, and actions such as processing money laundered by the cartels or extortion payments will face higher scrutiny. As the U.S. boasts a robust economy, cartel operations will likely face resistance, as transactions through American financial institutions and operations may experience asset freezes, depending on exposure.[12],[24],[31]

The new U.S. designations were recognized by Canada on 20 February 2025 when the Canadian government branded seven (7) of the cartels in question as terrorist entities. On the other hand, the Mexican government’s outlook on this matter is still uncertain. Relations between the U.S. and Mexico may be strained following the designations, as it presents the U.S. with enhanced jurisdictional powers to collect and act on intelligence in Mexico without the government’s consent, with the potential to be seen as undermining its national authority. The dispute regarding what other governments define as “terrorism” may potentially lead to fallout both internationally and domestically. Some FTOs (notably Hamas and Hezbollah) already attempt to use their political activities to feign legitimacy. However, if this recent series of designations sets a precedent, and other instances follow, American legal and federal systems may see a drastic increase in the number of qualifying FTO-related investigations.[32],[33]

[1] President Trump, Donald. (2025, January 20). Executive Order 14157: Designating Cartels and Other Organizations as Foreign Terrorist Organizations and Specially Designated Global Terrorists. Federal Register. Retrieved from https://www.hsdl.org/c/view?docid=894766.

[2] U.S. Department of State. (2025, February 20) Designation of International Cartels. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/designation-of-international-cartels/.

[3] Bureau of Counterterrorism. Foreign Terrorist Organizations. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/foreign-terrorist-organizations/.

[4] Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism. (2008, April 8). Immigration and Nationality Act Section 212. U.S. Department of State Archive. Retrieved from https://2001-2009.state.gov/s/ct/rls/fs/08/103399.htm/.

[5] Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism. (2008, April 8). Foreign Relations Authorization Act, Fiscal Years 1988 and 1989: Terrorism Definition. U.S. Department of State Archive. Retrieved from https://2001-2009.state.gov/s/ct/rls/fs/08/103401.htm.

[6] Federal Bureau of Investigation. Transnational Organized Crime. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/transnational-organized-crime.

[7] Schofield, R. (2015, December). Crime-Terrorism Nexus, and the Threat to U.S. Homeland Security. Naval Postgraduate School (U.S.) Retrieved from https://www.hsdl.org/c/view?docid=790384.

[8] Helfgott, A. (2023, October 24). El Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) – Explainer. Wilson Center. Retrieved from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/el-partido-revolucionario-institucional-pri-explainer.

[9] Drug Enforcement Administration. (2025, May). 2025 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA). Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved from https://www.hsdl.org/c/view?docid=895355.

[10] Felhab-Brown, V. (2021, September 15). Pipe dreams: The Taliban and drugs from the 1990s into its new regime. Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/pipe-dreams-the-taliban-and-drugs-from-the-1990s-into-its-new-regime/

[11] Manwaring, M. (2009, January 9). A “New” Dynamic in the Western Hemisphere Security Environment: The Mexican Zetas and Other Private Armies. US Army War College. Retrieved from https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1620&context=monographs.

[12] Witte, C. (2024, April 5) From the Halls of Montezuma: The Promise and Pitfalls of Designating Mexican Drug Cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations. Center on Law, Ethics and National Security. Retrieved from https://sites.duke.edu/lawfire/files/2024/04/Witte_Final_LENS_Essay_ Combined.pdf.

[13] U.S. Government Publishing Office. (2022, March 31). Assessing the Department of Homeland Security’s Efforts to Counter Unmanned Aircraft Systems, Joint Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight, Management, and Accountability and the Subcommittee on Transportation and Maritime Security of the Committee on Homeland Security, House of Representatives, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress. U.S. Government Publishing Office. Retrieved from https://www.hsdl.org/c/ view?docid=868550.

[14] Aldana, A. et al. (2022, November 10). Modeling the role of police corruption in the reduction of organized crime: Mexico as a case study. Scientific Reports. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-23630-x.

[15] Pring, C et al. (2019, September). Global Corruption Barometer: Latin America & The Caribbean 2019. Transparency International. Retrieved from https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/ 2019_GCB_LatinAmerica_Caribbean_Full_Report_200409_091428.pdf.

[16] Martínez-Fernández, A. (2021, February). Money Laundering and Corruption in Mexico: Confronting Threats to Prosperity, Security, and the US-Mexico Relationship. American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep30205.pdf .

[17] Congressional Research Service. (2024, October 1) U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation: From the Mérida Initiative to the Bicentennial Framework. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from https://www.hsdl.org/c/view?docid=892649.

[18] U.S. Department of State. (2021, March 30). 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Mexico. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved from https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/mexico/.

[19] Allen, B. et al. (2025, March 25). Understanding and Mitigating Legal and Compliance Risks Relating to Cartels and Transnational Criminal Organizations. Skadden. Retrieved from https://www.skadden.com/insights/publications/2025/03/understanding-and-mitigating-legal-and-compliance-risks-relating-to-cartels.

[20] Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). 18 U.S. Code § 2339B – Providing material support or resources to designated foreign terrorist organizations. Cornell Law School. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/2339B.

[21] Galdo, M. (2025, April 1). The Justice Department’s Multifront Battle Against Drug Cartels. Lawfare. Retrieved from https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/the-justice-department-s-multifront-battle-against-drug-cartels.

[22] Office of the Attorney General. (2025, February 5). Memorandum for all Department Employees: Total Elimination of Cartels and Transnational Criminal Organizations. U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/ag/media/1388546/dl?inline.

[23] 18 U.S. Code Chapter 96 Part I- Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/ 18/part-I/chapter-96.

[24] Knickmeyer, E. et al. (2025, February 19). Trump administration labels 8 Latin American cartels as ‘foreign terrorist organizations’. AP News. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/trump-cartels-foreign-terrorist-organizations-eb35567b69fc66f13f7f79fb90906a50

[25] Troutman Pepper Locke. (2025, February 24). US Declares War on Cartels: Historic Terrorist Designations Reshape Sanctions Compliance Risks. Troutman Pepper Locke. Retrieved from https://www.troutman.com/insights/us-declares-war-on-cartels-historic-terrorist-designations-reshape-sanctions-compliance-risks.html.

[26] Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2008). Executive Order 12333: United States Intelligence Activities. ODNI. Retrieved from https://www.odni.gov/files/NCSC/documents/ Regulations/EO_12333.pdf.

[27] U.S. Code. (n.d.). Title 50, Chapter 36 [War and national defense]. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/50/chapter‑36.

[28] U.S. Department of Justice. (n.d.). About OCDETF. Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/ocdetf/about-ocdetf.

[29] U.S. Department of Justice. (n.d.). Joint Terrorism Task Forces. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/terrorism/joint-terrorism-task-forces.

[30] The White House. (2025, January 20) Protecting the American People Against Invasion. The White House. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/protecting-the-american-people-against-invasion/.

[31] United States Attorney’s Office Southern District of Texas. (2025, May 30). Father and son indicted for providing material support to Mexican cartel engaged in terrorism. United State’s Attorney’s Office. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdtx/pr/father-and-son-indicted-providing-material-support-mexican-cartel-engaged-terrorism.

[32] Public Safety Canada. (2025, February 20). Government of Canada lists seven transnational criminal organizations as terrorist entities. Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-safety-canada/news/2025/02/government-of-canada-lists-seven-transnational-criminal-organizations-as-terrorist-entities.html.

[33] 118th Congress. (2023, June 07). Transnational Criminal Organizations: The Menacing Threat to the U.S. Homeland. Congress. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/event/118th-congress/house-event/116069/text.