Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South America (BRICS) Alliance and its Potential Global Impact

Intel and Analysis Team on May 2, 2025

Introduction

The alliance between the countries of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) has transitioned from one of economic cooperation to a geopolitical force that challenges Western dominance. Initially formed to facilitate collaboration among emerging markets, BRICS has gradually expanded its scope into political and security discussions. While not a formal military or intelligence alliance, cooperative efforts among member states suggest an evolving strategic framework. This white paper will examine BRICS’s military potential, economic advantages, intelligence collection concerns, and potential geopolitical implications for Western security.[1],[2],[3]

The G7 versus BRICS

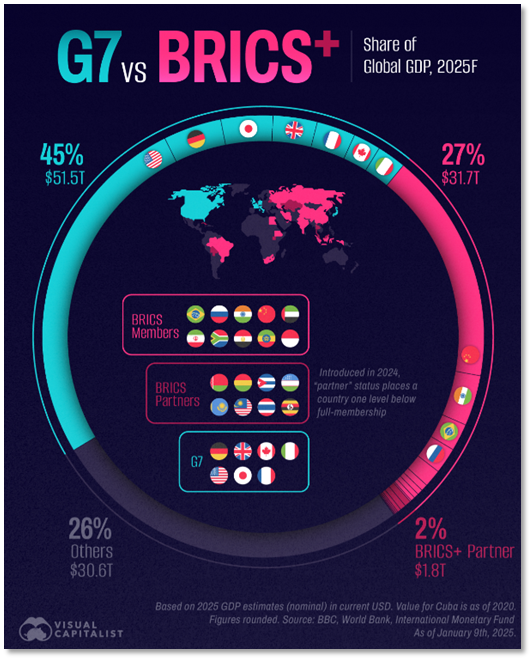

The G7 and BRICS represent two (2) distinct economic and political blocs with contrasting approaches to global governance. The G7 comprises advanced industrial nations and prioritizes financial stability, market-driven policies, and institutional frameworks that shape the global economy. Its influence extends across international financial institutions, trade agreements, and security alliances. Conversely, BRICS is primarily comprised of emerging economies. BRICS provides an alternative to the Western-led financial order while emphasizing economic cooperation among developing nations. The bloc seeks to challenge the dominance of Western financial institutions by promoting multipolarity in global decision-making and advocates for reforms in international governance structures.[4],[5],[6]

The advantages of the G7 lie in its established financial institutions, technological advancements, and ability to maintain stability in global markets. Economies like the United States, Japan, and Germany lead technological innovation and trade policies, keeping the G7 dominant in shaping international regulations. However, its shortcomings include limited representation of emerging markets and a perceived Western-centric approach to global economics. BRICS offers benefits in economic inclusivity by granting developing nations a stronger voice in global affairs. Its initiatives, such as the New Development Bank (NDB), provide alternative funding mechanisms that reduce reliance on Western financial institutions.[4],[5]

The geopolitical impact of both blocs remains a critical point of contention. The G7’s strong military alliances and security partnerships allow the group to exert influence on global conflicts, yet it faces challenges in maintaining diplomatic credibility among non-Western nations. BRICS, while advocating for a multipolar world order, risks deepening ideological divides between emerging and developed economies. As BRICS continues to expand its political and economic influence, its success will depend on its ability to foster mutually beneficial collaboration among its members while addressing internal disparities. Similarly, the G7 will likely adapt to global economic shifts and ensure its influence remains relevant amid rising competition from emerging economies. The interaction between these two (2) blocs will continue to shape international policy, economic stability, and geopolitical alliances.[4],[5],[6]

Economic and Political Influence

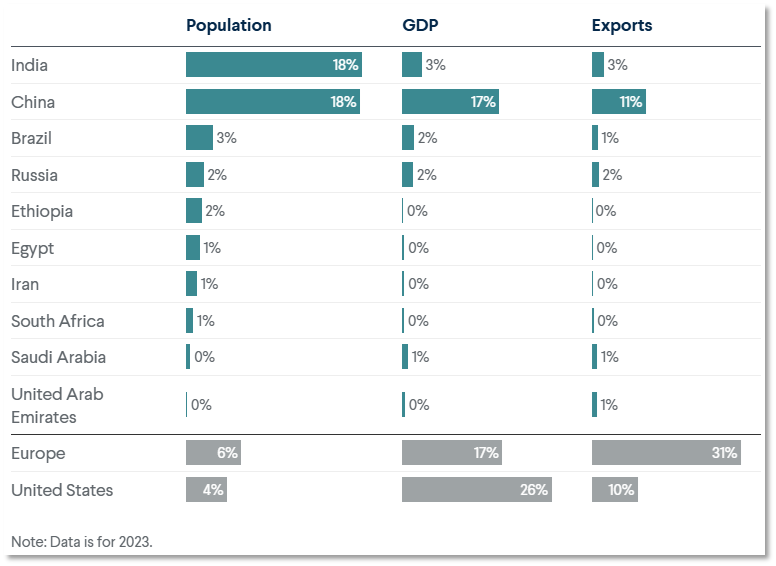

The BRICS alliance presents significant economic advantages by offering an alternative platform for emerging economies to shape global financial policies. Unlike the G7, which consists of advanced industrial nations, BRICS represents a diverse mix of rapidly growing markets. Collectively, BRICS markets contribute substantially to Global Domestic Product (GDP), with their trade accounting for over 25% of global GDP and approximately 40% of the world’s population. Through initiatives like the NDB and South-South Trade, BRICS nations finance infrastructure projects without the restrictive conditions imposed by Western financial institutions. BRICS countries are also advocating for the de-dollarization in international trade, opting instead for local currencies and alternative financial mechanisms that could reshape the global economic order and reduce vulnerabilities associated with Western monetary policies.[7]

Figure 1 – How BRICS compares to the G7 GDP[5]

Figure 2 – How BRICS Countries Compare in Population and Economy; 2023[2]

Aside from economic collaboration, BRICS has evolved into a powerful political force that challenges Western-dominated institutions and advocates for a multipolar global governance model. The alliance allows its member nations with opportunities to negotiate economic and political strategies independently from Western financial organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and The World Bank. BRICS reduces the dependency on Western economies by emphasizing cooperation among its emerging markets and fostering financial self-sufficiency, while strengthening regional development efforts.[2],[8]

Politically, BRICS enhances the influence of its members by fostering diplomatic initiatives that challenge Western-centric policies. Its expansion efforts allow developing nations to assert their interests in international affairs and ensure that their perspectives are considered in global decision-making forums. As opposed to the G7, which often reflects the priorities of established Western economies, BRICS advocates for governance reforms that address the concerns of emerging markets. By promoting trade, security, and environmental policy cooperation, the bloc empowers underrepresented nations and enables them to counter unilateral policies imposed by dominant global powers.[5],[8]

Despite its advantages, BRICS faces internal challenges that complicate its effectiveness as a unified bloc. Coordinated policymaking is challenging because member nations have stly different economic models, political systems, and strategic interests. China’s economic dominance within the group creates imbalances that affect decision-making policies and resource allocation while Russia’s geopolitical stance often complicates diplomatic efforts. Additionally, the absence of a formal governance mechanism limits BRICS’ ability to function as a cohesive political entity, restricting its ability to implement significant global policies effectively.[9]

As BRICS expands its reach, it also presents risks associated with global instability. The alliance’s efforts to de-dollarize trade and finance could disrupt financial markets and affect international currency stability and trade flows. Its deepening relationship with authoritarian regimes raises concerns about potential tensions with democratic nations and security frameworks. Furthermore, BRICS’s growing influence introduces ideological divisions that could increase political polarization and make global cooperation more challenging.[1],[7]

The most significant concern regarding BRICS’s economic and political influence is the potential to create a fragmented world order. If BRICS successfully develops parallel institutions rivaling existing Western-led organizations, global governance could become divided, increasing economic uncertainty and geopolitical competition. Its engagement with nations facing Western sanctions, such as Russia and China, further exacerbates international tensions and could potentially provoke countermeasures from established global powers. As BRICS continues to grow, its future will depend on whether it fosters cooperation or deepens ideological divides between emerging and established nations.[1],[9],[10]

The Foreign Nation-State Military Prospect of BRICS

The military prospects of BRICS as a foreign nation-state alliance remain complex. The bloc is not a formal military coalition, but increased defense cooperation among member countries is well documented. Russia and China, two (2) of the most militarily advanced nations within BRICS, have increased joint military exercises and defense technology exchanges, which have signaled a potential shift toward deeper security collaboration. India has engaged in defense dialogues with its BRICS partners while maintaining their strategic autonomy and balancing its relationships with their Western allies. The expansion of BRICS by including Iran and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), further raises questions about its future military posture and its countering of Western influence in global security affairs. While BRICS does not currently function as a unified military alliance, its growing defense partnerships and geopolitical positioning suggest it could evolve into a more structured security bloc, challenging traditional Western-led military frameworks such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).[1],[4],[11]

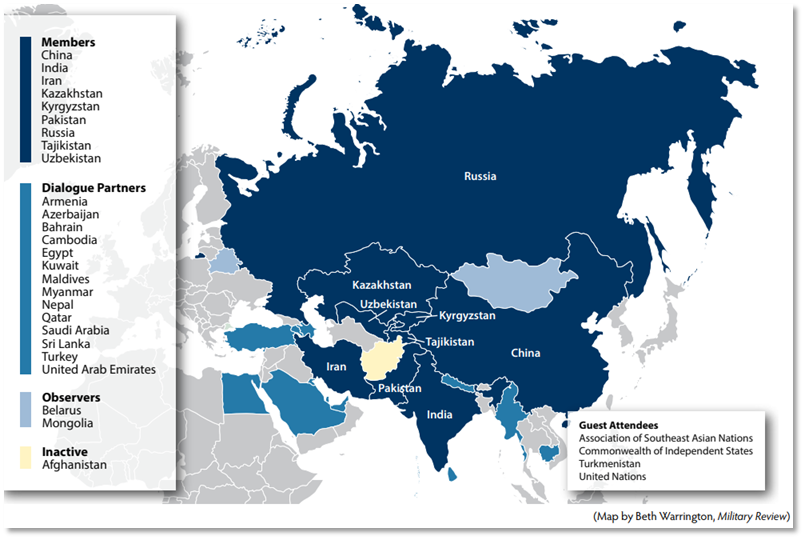

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is a vital geopolitical and security framework for Eurasia that enhances military coordination among its key members, such as Russia, China, and India. Established in 2001, the organization has gradually expanded its mission beyond economic and political collaboration to encompass defense-related efforts. Joint military drills, labeled as “Peace Mission exercises,” enable real-time coordination in counterterrorism operations, intelligence-sharing, and strategic defense planning. Russia and China are the primary military powers within the bloc and frequently conduct cyber defense exercises, simulated warfare scenarios, and advanced weapons development programs to strengthen their strategic alignment. While India actively participates in SCO-led defense initiatives, ongoing tensions, like its border disputes with China, have complicated deeper military cooperation. Despite these complexities, India continues to utilize the SCO as a platform for security discussions while maintaining its autonomous stance.[12]

Although SCO encourages defense interoperability, its ability to function as a cohesive military alliance is strained by diplomatic sensitivities and conflicting national interests. Russia and China advocate for greater security integration, while India remains cautious in balancing its partnerships with both Western allies and SCO member states. The Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) is a critical intelligence-sharing mechanism that strengthens surveillance, cybersecurity, and counterterrorism operation efforts. However, imbalances in military procurement, defense policies, and geopolitical strategies limit the bloc’s ability to operate as a unified defense entity similar to NATO. Adding to the complexities, including new members such as Iran, introduces further issues in aligning security interests. Despite these obstacles, the SCO remains an influential force in regional military cooperation that reinforces Eurasian security strategies and serves as a potential counter to Western-led defense alliances.[12]

Figure 3 – Shanghai Cooperation Organization Members and Dialogue Partners; 2023[12]

Mosi II, a joint exercise designed to strengthen naval cooperation and interoperability, took place in February 2023. Russia, China, and South Africa conducted joint maritime drills along the Indian Ocean coast near Durban and Richards Bay, South Africa. The exercise focused on disaster management, anti-piracy maneuvers, and air defense operations. The Russian Navy deployed the Admiral Gorshkov, a Project 22350-class guided missile frigate equipped with Zircon hypersonic cruise missiles designed for multirole operations equipped with advanced stealth technology, other long-range strike capabilities, and antisubmarine warfare systems, alongside a tanker ship. China contributed a destroyer, a frigate, and a support ship, while South Africa fielded a frigate and two (2) auxiliary vessels. The drills marked the second such exercise following November 2019’s Cape Town-based operation, signaling closer defense ties between the three (3) nations.[13],[14]

The exercise drew political controversy, particularly within South Africa. Opposition groups criticized the participation alongside Russia, accusing the ruling African National Congress (ANC) of favoring Moscow despite claims of neutrality. The timing of the drills coincided with the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, raising diplomatic concerns. South Africa’s Defense Ministry defended its involvement emphasizing the military benefits of joint security cooperation and maritime knowledge exchange. Viewed by some as a counterbalance to Western-led maritime alliances, the Mosi II exercise highlighted the growing complexity of global military partnerships amid shifting geopolitical landscapes.[13],[14]

Another example of BRIC member joint exercises, “The Maritime Security Belt 2025,” took place in the Gulf of Oman and involved naval forces from Russia, China, and Iran, and observer nations such as South Africa, Oman, Kazakhstan, and Pakistan. The drills were designed to enhance maritime security and counterterrorism and encourage naval interoperability, marking the second joint operation following a 2018 iteration. Russian, Chinese, and Iranian warships assembled at Iran’s Chabahar Port before launching the sea phase operation, which included hypersonic missile tests, air defense drills, and simulated hijacking scenarios. Russia deployed frigates and corvettes, including the Admiral Gorshkov, armed with Zircon hypersonic cruise missiles. China contributed destroyers and frigates from its Naval Escort Task Force, and Iran mobilized multiple vessels from both its Navy and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN). The exercise also focused on joint operations in shipboard security, countering unmanned aerial and surface threats, and coordinating multinational naval maneuvers. The exercise showcased a deepening military coordination between Russia, China, and Iran, raising concerns about evolving strategic alignments in Eurasian and Indo-Pacific security affairs.[15]

BRICS as a Foreign Intelligence Entity Against the U.S. and G7

From an intelligence perspective, BRICS members have demonstrated cyber capabilities, counter-surveillance strategies, and data-sharing agreements that could impact Western intelligence operations. China and Russia are known for their advanced cyber espionage programs and have collaborated on AI-driven intelligence gathering, satellite surveillance, and electronic warfare technologies. Additionally, BRICS’s push for de-dollarization and alternative financial mechanisms could limit Western intelligence agencies’ ability to track financial transactions, reducing transparency in global economic monitoring. BRICS does not function as a formal intelligence entity, but its strategic partnerships, military collaborations, and cybersecurity initiatives suggest a growing intelligence network that could challenge the dominance of U.S. and G7 intelligence frameworks.[16],[17]

BRICS nations like China and Russia have developed advanced cyber and intelligence capabilities and frequently engage in operations targeting Western governments and corporations. These activities range from cyber espionage, data theft, and disinformation campaigns to AI-driven intelligence gathering and electronic warfare. China has invested heavily in satellite surveillance, cyberwarfare units, and AI-powered intelligence systems, while Russia has refined its hacking operations, cyber sabotage techniques, and influence campaigns. Both nations have collaborated on cybersecurity frameworks and actively share tradecraft and intelligence methodologies to counter Western surveillance and digital dominance. The Digital Silk Road initiative spearheaded by China aims to establish secure digital infrastructure across BRICS nations and reduce reliance on Western technology while enhancing data sovereignty and cyber resilience. Russia continues to leverage its military intelligence units, such as the GRU, to conduct covert cyber operations, often targeting NATO and Western financial institutions.[17],[18],[19]

The intelligence node between China and Russia has evolved into a strategic partnership with both nations exchanging cyberwarfare techniques, surveillance technologies, and counterintelligence strategies. Russia’s GRU and SVR intelligence agencies have collaborated with China’s Strategic Support Force, focusing on military-technical espionage and cyber-enabled influence operations. Additionally, the Foreign Policy Research Institute has highlighted how China and Russia strategically employ information operations to undermine Western alliances like NATO by using disinformation campaigns and online propaganda.[17],[18],[19]

Additionally, BRICS members Russia and China have been actively working to establish a financial system independent of Western control or scrutiny while also aiming to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar and circumvent economic restrictions imposed by Western institutions. One (1) of the key initiatives in this effort is the development of digital currencies like Russia’s digital ruble and China’s digital yuan. Both are designed to facilitate cross-border transactions without using Western financial networks like The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT). The introduction of BRICS Pay, a decentralized payment system, further strengthens the bloc’s ability to conduct international trade using national currencies and digital assets, effectively bypassing Western financial oversight. These efforts directly challenge U.S. economic influence as they undermine the dollar’s role as the global reserve currency and limit the effectiveness of economic sanctions as a political tool.[20],[21],[22]

BRICS’s financial strategies raise concerns about sanctions evasion, economic disruptions, and the potential for alternative financial networks that operate outside Western or G7 regulatory frameworks. The digital ruble is positioned as a tool to help Russian businesses continue international transactions despite sanctions and to offer a stable alternative to traditional banking systems. Additionally, BRICS nations are exploring blockchain-based financial tools that could enhance transaction security and anonymity, making it more difficult for Western intelligence agencies to track financial transactions and trends. As BRICS asserts its financial independence, American and G7 intelligence efforts will likely focus on monitoring these developments and assessing their impact on global financial stability.[20],[21],[22]

BRICS has strategically expanded its global influence networks by strengthening diplomatic and economic ties with Saudi Arabia, Iran, and African states, positioning itself as the opposition to American and G7 geopolitical strategies. The bloc’s recent expansion welcomed Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the UAE. This expansion reflects a broader effort to consolidate influence across the Middle East and Africa. China and Russia actively engage in intelligence-sharing agreements, military collaborations, and economic partnerships with these nations, further developing the multipolar world order. Saudi Arabia’s addition to BRICS is another step towards shifting away from the exclusive reliance on U.S.-led financial and security frameworks, while Iran’s participation strengthens alternative trade and defense networks. BRICS nations have also leveraged African partnerships to secure critical resources, infrastructure investments, and intelligence cooperation, reinforcing their ability to challenge Western dominance in global governance. BRICS’s expanding diplomatic reach enables it to gather intelligence effectively and influence regional security policies to counter Western intelligence efforts. BRICS’s engagement with the Middle Eastern and African nations strengthens its ability to shape regional security frameworks, particularly in energy, counterterrorism, and defense technology transfers. As BRICS expands its footprint, its intelligence networks will likely evolve into a more structured framework that will challenge traditional Western intelligence dominance.[23],[24]

Conclusion

The economic rivalry between BRICS and the G7 continues to shape global financial dynamics. Both blocs are vying for influence over international trade and monetary policies. As of 2024, the BRICS nations collectively account for approximately $30.7 trillion in GDP, representing 29% of the global economic output, while the G7 maintains a position of $45.9 trillion, or 43% of global GDP. However, the projected growth rate for BRICS far exceeds those of the G7, with India and China accounting for most expansion efforts, potentially narrowing the economic gap by 2050. BRICS’s push for de-dollarization, alternative financial systems, and digital currencies threatens the G7’s control over global financial transactions and reduces Western oversight of international trade. The bloc’s increasing resource independence via adding Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the UAE strengthens its ability to challenge Western economic dominance in energy markets and commodity trade. As of now, BRICS lacks any formal form of a military alliance like NATO. For BRICS to become a structured military alliance like NATO, it must establish a formal security framework. This framework could include collective defense commitments, centralized command structures, and standardized military doctrines among its member states. The alliance would also need to expand bilateral military collaborations into multilateral training exercises, create a joint defense council, and integrate cyber warfare and intelligence-sharing mechanisms. However, such a transformation would pose a significant security risk for the G7 as Russia and China would most likely dominate a BRICS-led security pact. This could challenge Western geopolitical influence, disrupt surveillance operations, and expand arms development beyond NATO oversight. Additionally, BRICS’s economic independence being driven by the de-dollarization and alternative financial networks would reduce the Western leverage in global financial monitoring, making economic sanctions less effective. If BRICS successfully establishes a structured defense alliance, it could intensify the strategic competition with the G7 and increase political fragmentation.

[1] Patrick, S., Hogan E. et al. (2025, March 31). BRICS Expansion and the Future of World Order: Perspectives from Member States, Partners, and Aspirants. Carnegie Endowment For International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/03/brics-expansion-and-the-future-of-world-order-perspectives-from-member-states-partners-and-aspirants?lang=en

[2] Ferragamo, M. (2024, December 12). What is the BRICS Group and why is it expanding? Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-brics-group-and-why-it-expanding

[3] Garcia, Ana. (n.d.) Three Perspectives of BRICS Analysis. The American University in Cairo. Retrieved from https://bricspolicycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/BRICS-Analysis-compactado.pdf

[4] Adebisi, A. (2023, August 11). BRICS vs G7: Head-to-Head Comparison and Statistics. Investing Strategy. Retrieved from https://investingstrategy.co.uk/financial-news/brics-vs-g7-head-to-head-comparison-and-statistics/

[5] Rao, P. (2025, January 15). Charted: How BRICS Stacks Up Against the G7 Economies. Visual Capitalist. Retrieved from https://www.visualcapitalist.com/charted-how-brics-stacks-up-against-the-g7-economies/

[6] Conte, N. (2023, October 23). Charted: Comparing the GDP of BRICS and the G7 Countries. Visual Capitalist. Retrieved from https://www.visualcapitalist.com/charted-comparing-the-gdp-of-brics-and-the-g7-countries/

[7] World Reporter. (2025, April 14). How BRICS Nations Are Reshaping Global Trade Patterns and Reducing Dollar Dependence. World Reporter. Retrieved from https://worldreporter.com/brics-nations-reshaping-global-trade-patterns/

[8] Das, U. (2024, November 05). BRICS daringly autonomous model for financial sovereignty. Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum. Retrieved from https://www.omfif.org/2024/11/brics-daringly-autonomous-model-for-financial-sovereignty/

[9] Cossa, R. and Marantidou, V. (2014, November 19). Cooperation among BRICS: What Implications for Global Governance. Pacific Forum CSIS. Retrieved from https://pacforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/issuesinsights_vol15no4.pdf

[10] Muna, A. (2025, January). BRICS and the Global South: Redefining Power in a Multipolar World. BIPSS. Retrieved from https://bipss.org.bd/pdf/BRICS%20and%20the%20Global%20South_Abida%20Farzana.pdf

[11] Erkol, B. (2024, February 22). Will BRICS Become The New Warsaw Pact. Foreign Analysis. Retrieved from https://foreignanalysis.com/will-brics-become-the-new-warsaw-pact/

[12] Helms, S. (2024, January). The Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Army University Press. Retrieved from https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/January-February-2024/Shanghai/

[13] Chenglong, J. (2023, February 20). China, Russia, South Africa to hold 2nd joint naval exercises. China Daily. Retrieved from https://asianews.network/china-russia-south-africa-to-hold-2nd-joint-naval-exercises/

[14] Lesedi, S. (2023, February 23). Exercise MOSI II underway in South Africa. Military Africa. Retrieved from https://www.military.africa/2023/02/exercise-mosi-ii-underway-in-south-africa/

[15] Mahadzir, D. (2025, March 12). Russia, China and Iranian Warships Drilling Together in the Gulf of Oman. USNI News. Retrieved from https://news.usni.org/2025/03/12/russia-china-and-iranian-warships-drilling-together-in-gulf-of-oman

[16] Jiang, M. and Belli, L. (2024). Digital Sovereignty in the BRICS Countries. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://cyberbrics.info/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Digital-Sovereignty-in-the-BRICS_-Structuring-Self-determination-Cybersecurity-and-Control.pdf

[17] BRICS Today. (2025, February 28). The Digital Silk Road: Cybersecurity and Tech Alliances in the BRICS Bloc. Retrieved from https://bricstoday.com/the-digital-silk-road-cybersecurity-and-tech-alliances-in-the-brics-bloc/

[18] Galeotti, M., Eftimiades, N. and Herd, G. (2021, December 14). Russia and China’s Intelligence and Information Operations Nexus: Implications for Global Strategic Competition. George C. Marshall Center for Security Studies. Retrieved from https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/clock-tower-security-series/strategic-competition-seminar-series/russia-and-chinas-intelligence-and-information-operations-nexus

[19] Stradinger, J. (2024, November 5). Narrative Intelligence: Detecting Chinese and Russian Information Operations to Disrupt NATO Unity. Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved from https://www.fpri.org/article/2024/11/intelligence-china-russia-information-operations-against-nato/

[20] Congressional Research Service. (2018, February 8). Digital Currencies: Sanctions Evasion Risk. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IF/PDF/IF10825/IF10825.3.pdf

[21] FINCRIME CENTRAL. (n.d.). Russia’s Tools For Sanctions Evasion: The Digital Ruble and BRICS Currency Plan. Retrieved from https://fincrimecentral.com/russia-digital-ruble-brics-evade-sanctions/

[22] Ciccomascolo, G. (2025, March 27). BRICS Pushing Forward With Digital Cross-Border Payment System, Russia’s Finance Minister Confirms. CCN. Retrieved from https://www.ccn.com/news/business/brics-digital-cross-border-payment-system-russia-finance-minister/

[23] Zaccara, L. and Battaloglu, N. (n.d.). BRICS Membership: Gulf States’ Strategic Pivot in Shifting Global Dynamics. Gulf International Forum. Retrieved from https://gulfif.org/brics-membership-gulf-states-strategic-pivot-in-shifting-global-dynamics/

[24] Pillai, K. and Savio, T. (n.d.). The Latest BRICS’ Expansion, But Probably Not the Last. The International Affairs Review. Retrieved from https://www.iar-gwu.org/blog/iar-web/the-latest-brics